Indian democracy has succeeded for a range

of reasons — an enlightened political leadership which wrote a remarkably progressive

Constitution; political parties which have played the democratic

game within rules; an aware electorate which has kept the parties on

their toes; a vibrant civil society which has championed rights and

justice; a free press which has kept citizens informed and kept power under

check; and, institutions which have fulfilled constitutional

obligations. Among these institutions, India’s independent judiciary

occupies a place of pride. For the most part, it has defended individual

liberty and protected fundamental rights; it has expanded the

idea of justice and pushed the State to support the vulnerable; it

has resolved disputes between the State and citizens, among citizens,120

between the Centre and states, and between states; it has stood as a

pillar in defence of the basic structure140 of the Constitution; it has served as a check on executive

excesses; and it has given hope to all stakeholders,160 from the powerful to the weak, that

there will be justice. That is why a robust and independent

judiciary is so critical to India’s constitutional functioning. However, in

recent years, there appears to be a trend which suggests a much closer

alignment between the judiciary and the executive than is healthy for a

system based on checks and balances. The judiciary is far too important

for anyone to assume it is perfect. On the basis of the principle

that anything240 can be improved, this trend and its specific manifestations need

further discussion. The first is the incentive structure of the judges. This is

crucial to safeguarding the independence of the institution and maintaining its

credibility. Though the executive has been280 able to exercise influence, both directly

and indirectly, over the collegium process, the judiciary has

fiercely guarded its right over appointments. But there is another way in which

judges may not be entirely free of external incentives while

exercising their320 duty. The prospect of being appointed to Government

positions after retirement could be a way in which the executive exercises

control over an otherwise independent judiciary, in countries with judicial

term limits. This trend appears to have only continued post-2014. 360

When a former Chief Justice of India ends up becoming a Member of Rajya

Sabha or a Governor nominated by the President on the advice of the Council

of Ministers, doubts grow in the minds of citizens. Unless this

incentive structure for judges is changed either through a prolonged cooling-off

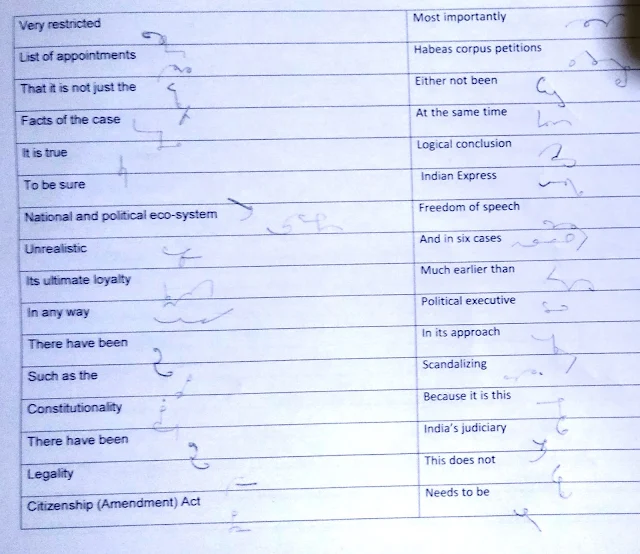

period or a very restricted list of appointments, the420

perception that it is not just the legal facts of the case that

determine a final judgment will prevail. The second issue is what legal

scholars have termed as “constitutional evasion”. It is true that the

Supreme Court is overburdened. But there appears to be a pattern where the

timing of when a matter is taken up, or when an order480 is

delivered or judgment is pronounced, has been convenient for the executive.

To be sure, the judiciary itself operates in a larger national and

political eco-system and to expect judges to operate in a vacuum may be unrealistic.

But its ultimate loyalty has to be to the Constitution, without being

swayed in any way by either public opinion or political thought. There

have been a range of critical cases such as the constitutionality

of the changes in Jammu and560 Kashmir, the legality of the electoral bonds, the Citizenship

(Amendment) Act, and most importantly, habeas corpus petitions

which are quite central to Indian democracy. But these have either not been

taken up, or taken up after prolonged gaps, or not concluded.600 At

the same time, issues that appear aligned with the political preferences of

the executive have reached their logical conclusion. On Saturday, The Indian Express reported

that out of 10 cases which were to do with freedom of speech, the640

court upheld the right or gave relief in cases where the State and the

petitioner argued on the same side and in six cases where the State

objected, there was no relief to the petitioner. Even in Ayodhya Ram Temple

Case, the Supreme Court should have delivered the long-pending verdict much

earlier than it finally did; but the timing700 of the final verdict worked well for the political

executive. None of this may be deliberate, but it creates apprehensions

which720

the judiciary can well do without. The third issue is that in its approach

to contempt, the Supreme Court appears to have adopted a somewhat rigid view.

As debates elsewhere in constitutional democracies have evolved, the charge of scandalizing

the court has come to lose its validity. Yes, when there is an attempt to

obstruct justice, when there is outright defiance of a court order by any

party, when there is an effort to influence the legal process through

extra-legal800 means like bribing stakeholders, the Supreme Court must

step in. But when there is criticism of the court, or of judges, then courts

must be open because it is this healthy criticism of institutions that

help them improve in a840 democracy. Certain trends show that parts of the judiciary

may not be working as independently as mandated. Placing oneself above

criticism will not help the institution and its legacy. India’s judiciary

is a key pillar which has to be fiercely independent and be seen as such. This

does not mean that it needs to be consistently adversarial to the

executive, nor does it mean that it should be far too friendly

with the executive. A relationship of respect but distance between the

judiciary and the executive and a relationship of openness between the

judiciary and the citizens is the most effective way for democracy to thrive

and for the institution to regain its credibility.

The new National Education Policy,

2020 has960 been received with broad praise. The goal of universalization

of early childhood care and education and the focus on achieving980

universal foundational literacy and numeracy is especially laudable. The

challenge now lies in translating policy into action on the ground at scale.

Most policy suggestions are not new as several State Governments have

been trying hard to implement such reforms. However, the lack of consistent

political will and the slow pace of adopting emerging technologies have stymied

these efforts. We know how to educate children, as is evident in elite schools.

But our inability to do so for all children is due to the failure in

understanding the role of politics and technology. How are parents from

less-privileged backgrounds expected1080 to understand the value of the current

reforms such as curriculum overhaul, teacher-training or activity-based

learning in schools? These are all hidden behind school walls, parents are not

involved, and the visible impact of better education manifests later in life. 1120 As

a result, the public-school system has lost the perception battle to the

private system. In private-school system, parents are the most critical

constituency. The private-school system takes huge pains to dazzle parents

through fancy brochures or computer labs. Public educators tend to be poor

publicists. Unfortunately, National Education Policy ignores the

political-economy aspects of education and the critical need to involve the

parent as a teacher and voter. Parents are only mentioned 25 times, as compared

to 221 mentions1200 for teachers. It is because of the opaqueness of progress

and lack of value realization by the constituents that the politicians across

the spectrum have not paid attention to education, as compared to other

sectors such as infrastructure and skills training. Education reform

attempts come and go, based on the whims and fancies of officials and

their unpredictable tenures. Even1260 beyond political incentives, it is vital that parents

are involved directly in the learning process of their children.

Such1280 home effects have been shown to be key drivers of learning

outcomes. Parent and community engagement is not just a political

carrot, but also essential for the child’s progress. Models designed to include

teachers as key facilitators for parent interactions also increase community

respect for teachers, which is another key objective of the National Education Policy.

Across the board, teachers are motivated by how parents value them more,

realize the positive things happening in school, and express their admiration

for their efforts. Recently, we see that, when parents notice education

improvements, it translates into political popularity. Delhi, Punjab,

Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh are all early examples. In this context,

governments and politicians will only do the hard slog to translate National1400 Education

Policy into reality if their efforts are easily visible and impressive to

parents, a key voting bloc. A natural question is: How can we bring

parents on board and achieve universal foundational literacy and numeracy

throughout India? How1440 can government achieve this scale with a high return on investment?

The answer is the digital revolution. India is expected to have 820 million

smartphone users by 2022 and, for the first time, India has more rural

Internet users than urban. This is the time to use these tail winds and

adopt innovative low-tech to enable school-home connections and engage parents

where they are. Specifically, school systems need to leverage technology and

mass media communication to show parents daily and directly that they are

investing in their children’s success, and that the child is actually

learning. Technology can play a key role in bringing about this behavioural

change by implementing the Aspiration, Information and Measurement framework.

We can use social media platforms such as Facebook and Youtube to

bring about awareness, we can leverage messaging platforms such as WhatsApp

and Telegram to disseminate educational content to learning communities, and

we can use artificial intelligence to measure these learning outcomes at1600

scale.